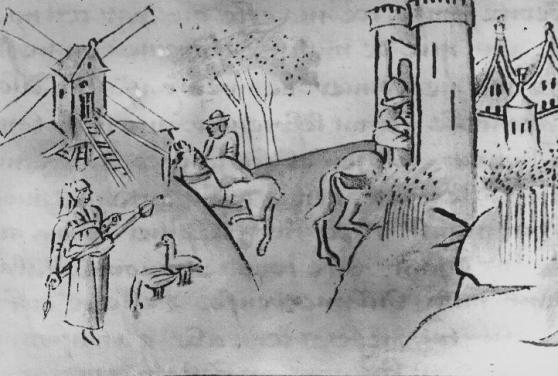

Something you notice in medieval spinners is that whenever they spin they seem to be using distaffs to hold the fibre. The link with the distaff and spinning was so strong that the female side of the family got the name the “distaff side”. It’s not just medieval Europe, either. In my research of cultures around the world anywhere I find people still using a spindle to produce thread I tend to find them using a distaff. Compare this to cultures where our thread and fabrics are produced in factories and spinning is more of a hobby there is a tendency not to use distaffs. Or to use a small one around the wrist instead of a large stick.

I think the reason for this is in cultures where they must spin with a spindle or go naked, spinning is a constant task. I read stories of children spinning while playing, women spinning while walking to the market or watching sheep.

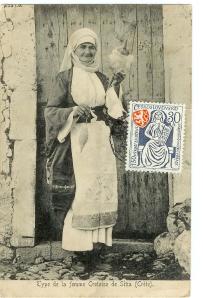

You can see here this lady has put up her spindle to feed the chickens, but she was probably spinning on her way to the chickens.

The key here is spinning for a length of time and spinning while being active. Yes, you can carry a basket full of wool and tuck it up into your sleeve as you go, but I guess putting it on a big stick keeps it all together. If you’re only spinning as a hobby you’re more likely to do it while sitting in front of the telly. Even if you spin during a long car journey you’re still in the one spot.

The spinning I’ve been doing involves me having my stash of fibre on the ground next to me and me picking up more as I need it. I guess this is the same thing as carrying it around in a basket or an apron. It’s not that inconvenient and I think a great big pole to lug around WOULD be, even if it keeps everything together. Why did the use a distaff? Well, for the use of one to be so wide spread throughout history there must be some good things about it. And there’s only one way to find out…

Enter the wooden dowel from the craft shop.

Because I don’t want to go to a heap of effort for my first distaff I bought a wooden dowel from a craft shop, popped a length of flax tow over it and criss-crossed a bit of ribbon over it to secure it.

The verdict? Well, It’s not too bad. Not bad at all. In the picture above I’ve had it stood in a corner and been spinning from it and it works pretty well. I thought it would be far too short to put through my belt, but when I spun down to the length that I had above I stuck it through my belt. The first time was a disaster but the second time it worked perfectly. The difference? The first time I tried it with a modern belt containing elastic at my natural waist and the second time I used my leather belt I wear with my 1480 dresses and I wore it on my ribs where the high waist of my Italian dresses sit. The high waist brought it that much higher and out of the way of most of my body’s curves. It worked really well. I think a longer stick would work better at my natural waist with a proper leather belt.

As you can see from the picture I made sure to draft evenly from both sides of the distaff, but that was pretty easy to do. Using a distaff is quite different because instead of holding the fibre in your left hand you have a spare hand to hold it so your left hand can pull the fibre away from the supply when you draft it. When I was drafting the flax from my shoulder I found that I had to keep picking up the fibre supply and moving it away. I have fewer tangles with the distaff and I never have to worry about getting a new lot of fibre. I only have to worry about joining the thread when I break it, not each time when I run out of fibre. What else can I say? I love my distaff. It helps when I’m sitting doing nothing but I can also see it helping if I was wondering around doing stuff.

Here’s how my spinning is going. You cans see how crappy my spindle is, but it works! That’s all for now. Next time I’ll be re-vamping my spindles with clay whorls.